It is difficult to imagine that the area was completely covered by the sea a very long time ago when you look at the present-day landscape. The geology of the Sancerre region essentially dates back to the Mesozoic Era (Upper Jurassic, Oxfordian and Kimmeridgian stages, dating back 163.5 to 152.1 million years), with other formations during the Tertiary Period (Early to Middle Eocene dating back 56 to 33.9 million years).

It was a very slow process for the terroirs that we know today to be formed, either by the accumulation of sediments (including marine sediments containing a high proportion of invertebrates), or by erosion.

Yet the history of the Sancerre region began with an out-of-the-ordinary geological accident that proved to be the source for the typicity of our terroirs. This natural space formed by the Loire’s mid-river basin, was subjected to a major geologic enigma, that of the Magnetic Anomaly of the Paris Basin. This geological accident resulted in the creation of the “Sancerre fault”, running in a Nord-10°-East direction, which enabled geological formations from different periods to come into contact with one another. The principal accident caused numerous other relatively parallel faults, but with less displacement (such as the Thauvenay fault, which harbours a small strip of sands, multicoloured clays and ferruginous sandstone dating back to the Barremian age of the Cretaceous).

As with the phylloxera epidemic that ravaged the vineyards beginning in 1885, the growers, along with the help of Mother Nature, have been able to use this accident to their advantage !

Upper Devonian : An intracontinental rift was filled with a sea

The Sancerre region was affected by the creation of an intracontinental rift (collapse of the Earth’s crust) which was filled with an inland sea.

Mississippian stage of the Lower Carboniferous : closure of the rift and formation of the bedrock of the Sancerre region

The collision between the two large subcontinents, Armorica and Gondwana (which together formed Pangea), closed off the ocean to form what is called the Eovariscan suture to make up the early geological bedrock of the Sancerre region, which was subjected to incessant movement. At the time, the region culminated at an altitude of over 8,000 m. Located much further south than today, the climate ranged from semi-arid to tropical.

During the Secondary Era and the Jurassic period (from 201.3 to 145 million years ago), tectonic activity stabilized and a considerable part of Europe was covered by the sea : this long period of marine sedimentation resulted in thick accumulations of shellfish and coral debris.

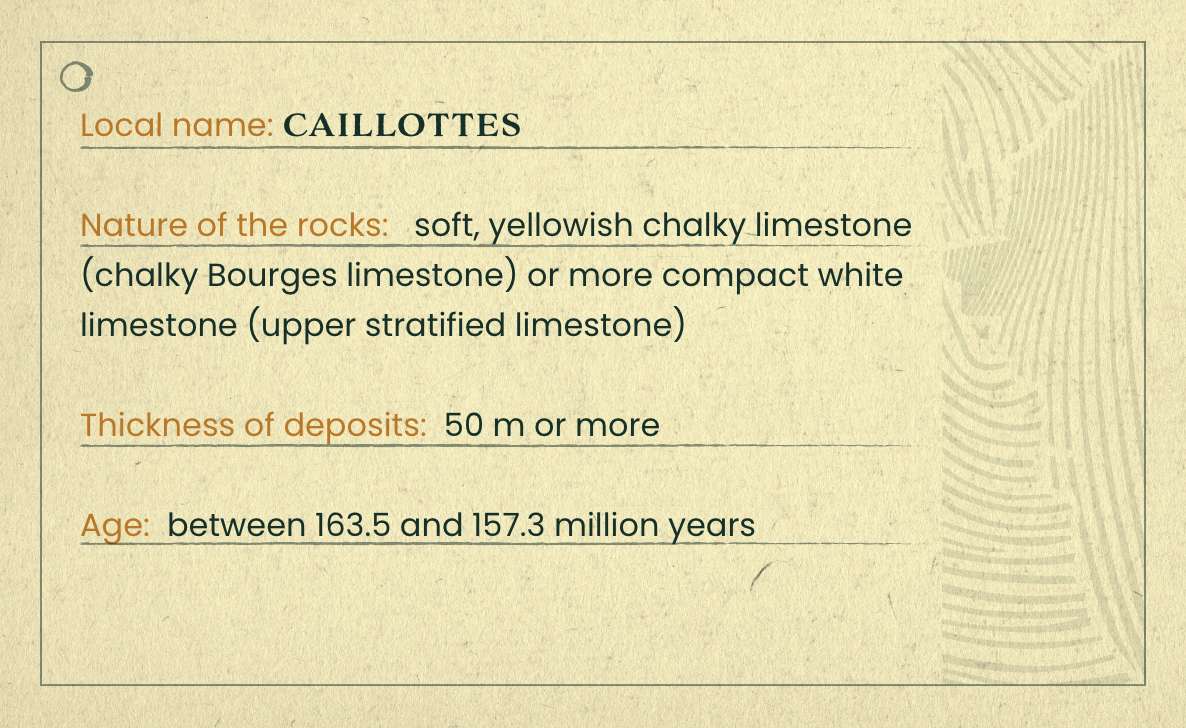

What can be seen in the Sancerre region’s geology today may be traced as far back as this period (Upper Oxfordian, between 163.5 and 157.3 million years ago), when a vast warm sea covered the area and, according to the oxygenation of the water and the abundance of its biodiversity, intensive sedimentation contributed to the formation of different types of limestone (chalky Bourges limestone between layers of stratified limestone).

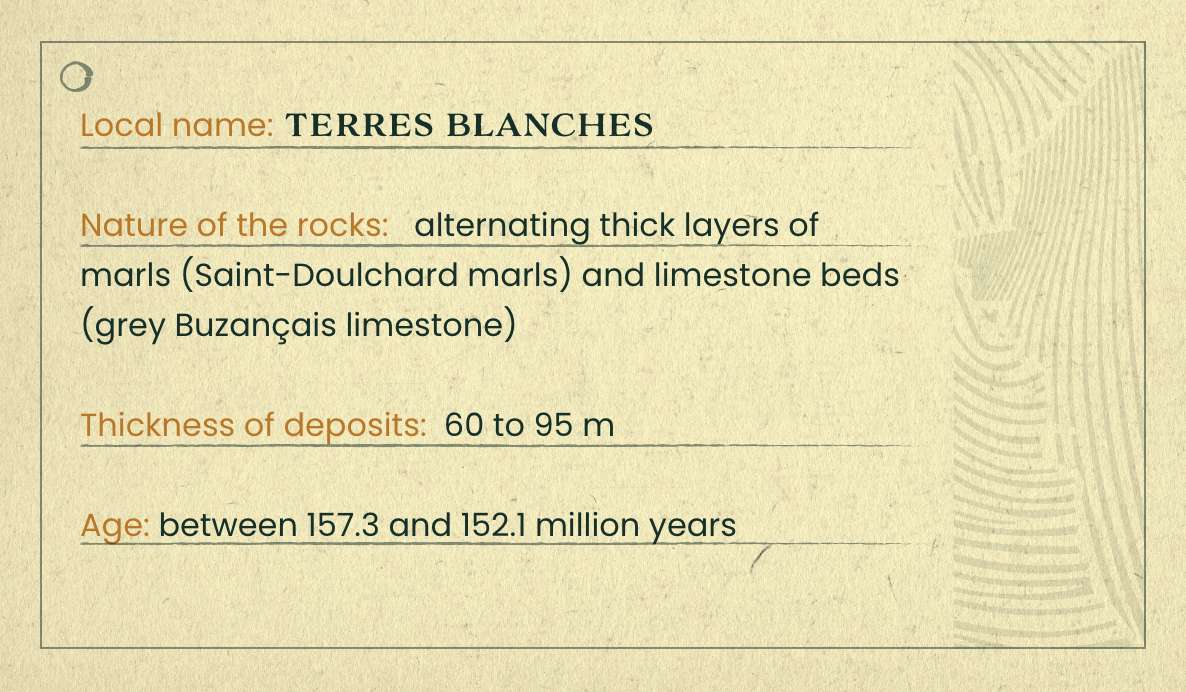

The sea was still present with even more oxygen : the resulting formations were composed of grey limestone during the Lower Kimmeridgian (Buzançais limestone, which broke up into small blocks) or marls made up of an accumulation of muds in a deeper sea during the Upper Kimmeridgian (Saint-Doulchard marls).

The sediments that formed at this time testify to the filling in of the area and correspond to Saint-Martin d'Auxigny limestone.

At first, the sea retreated from the Sancerre region completely and the entire upper layer of the Tithonian deposits began to be deeply eroded. An inlet then filled the region during the Lower Cretaceous, nevertheless prior to that, there were some limestone formations with ferruginous oolite, multicoloured clays and ferruginous sandstone, but also with the return of the sea (in the form of a delta), fine sand with sandstone veins, blue clay in Myennes (which was later used by potters in La Borne and La Puisaye) and multicoloured clays and sands in la Puisaye.

The sea was still present and its temperature was particularly high, resulting in sandy clay formations, followed by Vierzon greensand, clayey chalk and ostraceous marls (with a remarkable accumulation of fossilized oysters). The sea retreated from the Sancerre region once and for all at the end of the Cretaceous.

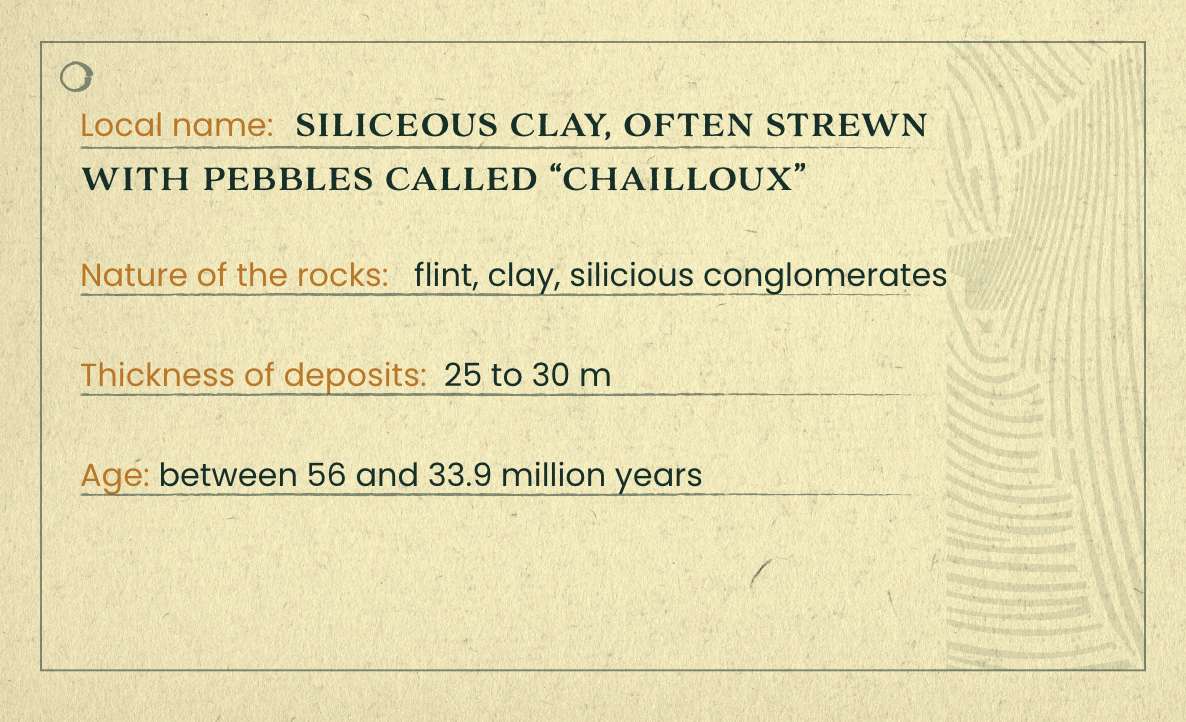

In the Tertiary Era (which began approximately 66 million years ago), the climate was hot and a tropical rainforest covered the region. The pre-existing sedimentations, now out of the water but subjected to heavy rains, were severely eroded, while being progressively transformed into flint-based residual complexes. Thus, during the Eocene (between 56 and 33.9 million years ago), the limestone deposits dissolved and liberated clay residues in the form of flinty clay or flint scree.

A new alpine fold occurred locally and affected the entire Massif Central region. In the Sancerre region, this resulted in the resumption of tectonic movement along existing faults (principally the Sancerre and Thauvenay faults). The major consequence was the sinking of the eastern Burgundian block, which ended up being 150 m lower in altitude than the hilly topography of the Sancerre region. The other consequence of these tectonic movements, along with the rather hard nature of the lower formations, was the formation of the tortuous relief of the hills, whose altitudes range between 200 and 400 metres. These include the Sancerre hill and Orme-au-Loup hills (overlying hard bedrock composed of flint conglomerate) et the Pays-Fort cuesta visible to the west (overlying hard Tithonian limestone bedrock).

The Sancerre region is subject to periods of glaciation, accompanied by powerful winds that erode the relief. Intense frostbite has led to the colluviation of flint fragments on certain slopes to the east of Sancerre (notably on the slopes of Orme-au-Loup and Pierre Coupilière).

We can therefore identify at least fifteen distinct geological periods that overlap, interlock and co-exist in the Sancerre region. This gigantic geological layer cake makes this micro-region an ensemble of remarkable, unique terroirs for viticulture.

In addition to the geological aspects, there are also complementary differences based on the physical, chemical or biological characteristics of the topsoil whether it be brown limestone, calcimorphic (abundance of limestone), or clay soils that contain varying proportions of humus and organic matter, etc. All of the above factors yield subsoils that contribute to this mosaic, which are expressed in a multitude of nuances by the growers who showcase our local grape varieties.

Indeed, the hundreds of millions of years of geological upheaval and erosion have created an incredible mosaic of subsoils that overlap one another. To simplify matters, three main families of terroirs stand out and define the identity of our wines, from west to east :

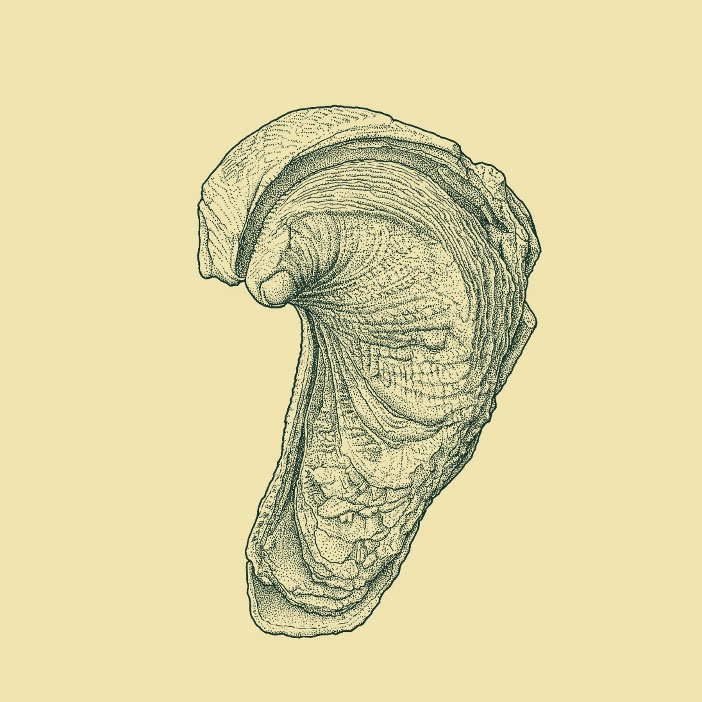

Fig. 223. Oysters (2.)

Fig. 812. Bivalves (1.)

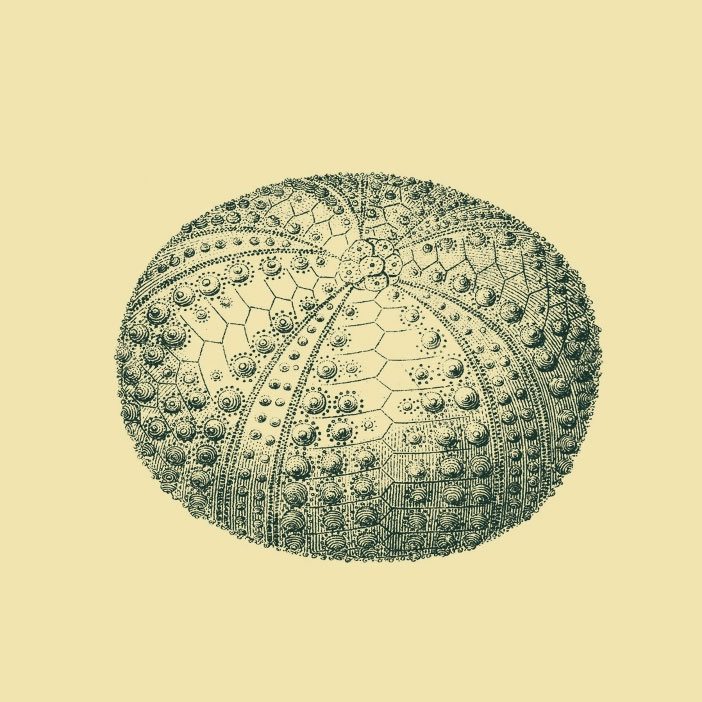

Fig. 447. Sea urchin (1.)

For millions of years, marine sediment deposits will overlap, trapping a wide variety of invertebrates (oysters, bivalves, sea urchins).

These successive deposits, with a thickness of a few centimeters to more than a hundred meters, are reef or lagoon, both marine and oceanic.

Located on the highest, westernmost hills of the Sancerre region (Sainte-Gemme-en-Sancerrois, Sury-en-Vaux, Maimbray, Verdigny, Chavignol, Amigny, Bué, Crézancy-en-Sancerre, Veaugues and Montigny), composed of calcareous clay dating back to the Jurassic and Kimmeridgian ages. These marls represent approximately 40% of the surface under vine and are composed of 70% clay and 30% limestone. These terroirs are very rich in shell fossils and whiten when they dry. They overlie the “caillottes”.

Located between the “terres blanches” and Sancerre, very stony and calcareous, this limestone also represents 40% of the surface area under vine and are the oldest formations that can be seen today on the surface as a bed of flat frost-shattered stones. The rain washes away the soil around the base of the vines so that only the stones remain visible, making these terroirs identifiable to the naked eye.

These formations lie on either side of the Loire River and are found on the tops of the hills in the eastern part of the appellation (Sancerre, Saint-Satur, Ménétréol-sous-Sancerre, Thauvenay and Bannon ; as well as on the La Pierre Coupilière, L’Orme-au-Loup, and Le Roc hills). Riche in flint, they ensure that the vines receive continuous heat. They represent approximately 15% of the area under vine and correspond to the more recent formations.

The soil is therefore of utmost importance and the vines that plunge their roots deep down bear its unique characteristics. Obviously, in addition to that hallmark, the plots’ exposure to the sun and the work of the growers must also be taken into consideration, which culminates in a style of wine that is specific to each estate.

Learn more about tasting